Alerting: Expectation vs Reality

Let’s say you’ve a moderately complex system that your team has been working on for the past couple of years. It works well and the users are generally happy. But now-and-then you hear user complaints about system being down or not able to use a feature. You think perhaps you need be more proactive in catching these issues than being reactive to user complaints.

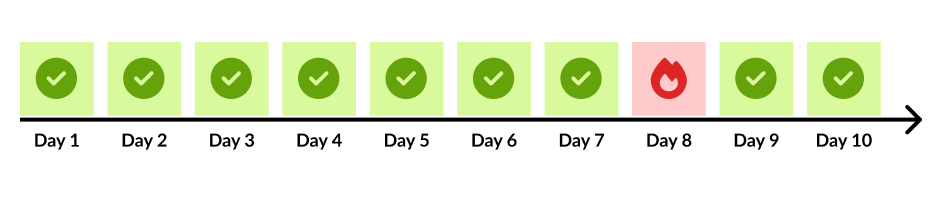

In your mind, you think the system works well for most of the days, and goes down or causes errors for couple of days a year.

To be more proactive in catching errors, you implement monitoring and alerting for your system, and this is what you see now:

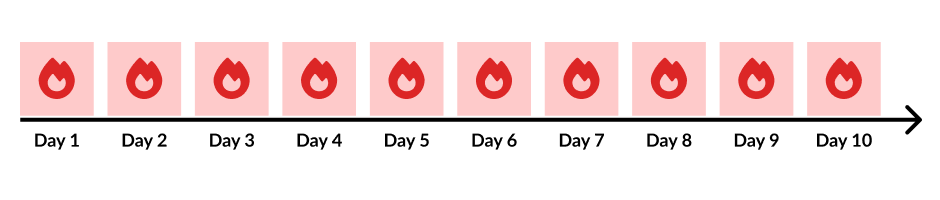

You expected less frequent issues in your system, but looks like your system is on fire every single day!

Why is there a big gap between expectation and reality?

- Not all users report errors. Some might stop using your product and turn to alternatives. Only a few dedicated users were giving you feedback before.

- Some of the errors you’re seeing are edge cases that escaped your QA process - there’s only so much manual or automated testing can catch.

- Some errors might be from endpoints or services that are not that critical to the users, so the users didn’t report it before.

- Other errors might be duplicates. If you’re using microservices architecture, then if there’s an error in one service, all the upstream services that depend on it would also throw errors.

Alert fatigue

One big consequence of dealing with alerts everyday is that your team gets numb to them. This is called alert fatigue. If everything is on fire all the time, one more fire doesn’t make much of a difference - but this fire can be your authentication system being down and none of your users can login! Not only you’re missing out on alerts, your team also gets mentally tired and unable to focus on other tasks.

What can we do about this?

- Instead of having the same set of people looking into the alerts, rotate people so they have time to recover.

- Triage the issues first. Spend some time understanding the business impact of the error. This would help you prioritize which errors to fix first.

- If the errors are not important, you can silence them either temporarily (for your team to catch up to more important errors) or permanently.